Having recently relocated to London, I have been trying to take full advantage of the classical music scene here, with the intention of deepening my knowledge of the classical guitar, its sound, its music and players. The only difficulty is that often, when I attend these concerts, I’ve already done a full day's work in the workshop. However it’s worth it as I’m receiving a well rounded education in not only guitar music, but there are opportunities to explore all music and other instruments as well. In my April newsletter, I wrote briefly about some of the concerts I attended. Those events included a recital by Jack Hancher, and two really fascinating events at the Royal Academy of Music. I will paste in my thoughts on those past concerts at the bottom of this post.

https://www.ahmeddickinson.com/

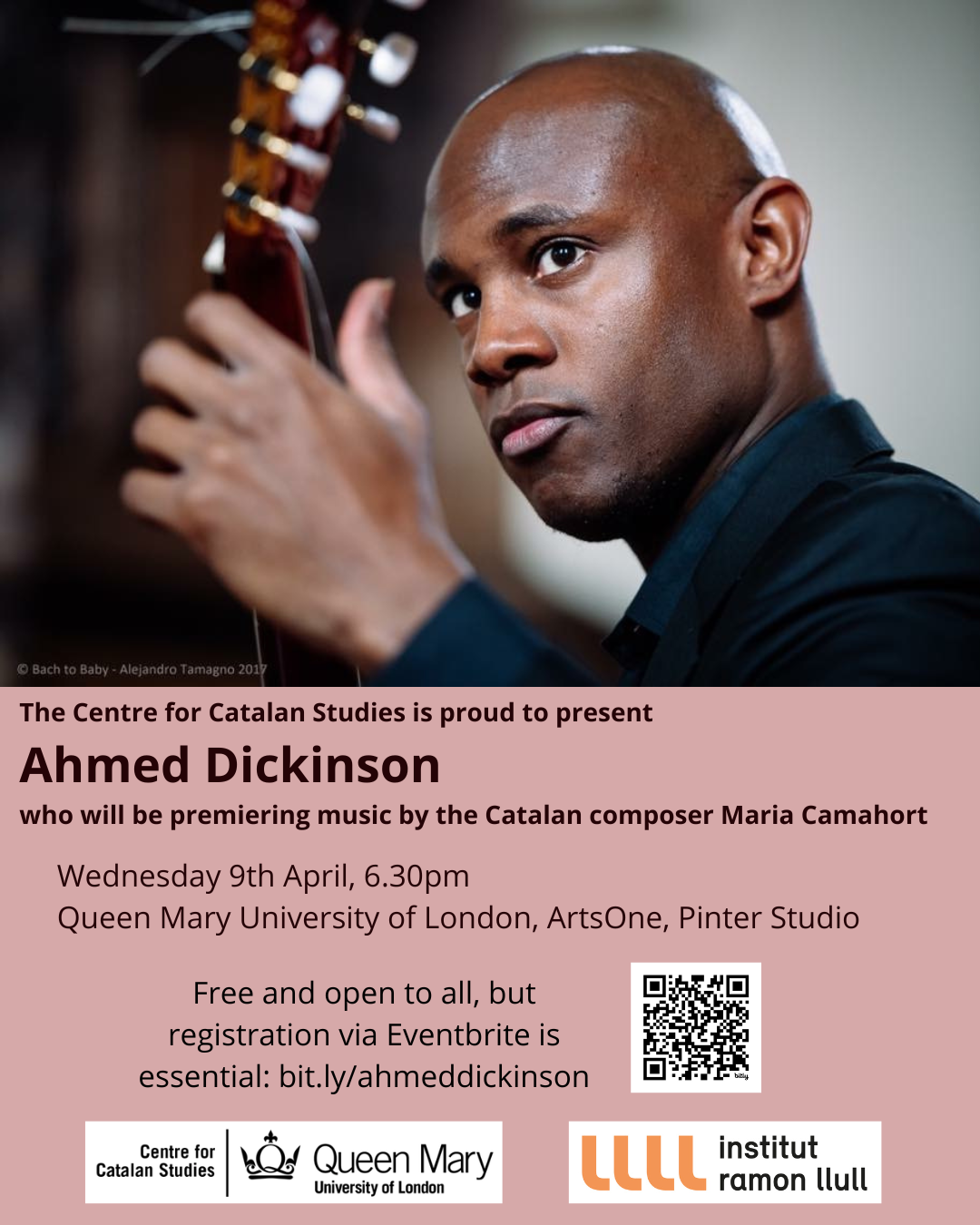

Ahmed Dickinson concert, Eduardo martin Music

Today though, I feel particularly inspired to write about two concerts which really got me thinking, and left me feeling particularly inspired. One was a concert by Ahmed Dickinson focusing on the music of Maria Camahort and Eduardo Martin. The other was a concert titled Great Modern Masterworks of Classical Guitar, featuring three advanced students at the Royal Academy of Music.

I had been particularly looking forward to attending Ahmed Dickinson’s concert one evening earlier this month. I made the fateful decision to walk from my workshop to Queens Mary University (where the concert was being held). This long walk took me through the very centre of London, past Brick Lane, past a long enticing exotic food market and finally I arrived just in time.

The concert was set in a small, intimate theater, perfect for the classical guitar. Though it was to particularly focus on the music of Maria Camahort, in the first half Ahmed played music by Eduardo Martin. Two suites were played, Album of Innocence and Songs of the Calendar, both were long suites made up of many shorter pieces. They were very easy/pleasing to listen to. There are a couple of pieces within the suites that I have continually sought out in the weeks following the concert, and might try learning myself.

I should mention that the concert was organized by the Centre for Catalan Studies and the music of that region was a theme of the concert. So Spain was on my mind while listening to these pieces and although I haven’t been to Catalonia, I found myself recalling my experiences in Valencia, Madrid and Granada. Each short piece within the suites had a different character, and evoked a different type of memory, some I thought I had long forgotten. It was a brilliant experience.

Some experiences that I recalled include memories from a trip in Valencia. I went there to buy some wood in 2018/2019. After purchasing the wood the owner took me to a cafe and we had a three course meal. The cafe was at the centre of an industrial warehouse park where the wood dealer was based, and was a popular spot for all the workers there so it was a really authentically Spanish place. Other memories included getting lost on the way there, but managing to find the correct warehouse because it smelled so strongly of cedar; random recollections of being in Granada; a night spent in Barcelona (so I have been to Catalonia! I had forgotten)...

The music of Maria Camahort

After the interval, the music of Maria Camahort was coming up, but before that was a video in which the composer herself spoke about career and music. Maria is a guitar, composer, teacher and performer. She was based in London for 10 years but returned to Barcelona in 2018, so her work is inspired by both places. As well as being really interested about her career and work, I admired/envied the articulation with which she spoke about her work, and hope I can do the same when people ask me about my own work.

I was really struck by Maria Camahort’s music. It feels as though she has her own highly developed musical language. I am someone who sometimes finds modern classical music difficult to listen to, but Maria’s music conveyed a sense of peace, introspection, thoughtfulness and really was beautiful to listen to.

Sometimes when I listen to modern classical music, it all sounds like madness. Sometimes, a composer jumps between tonality and atonality for contrast, but it only sometimes works and somehow after the modern sections of music the tonal tradition style can sound somehow cheaper in contrast. I’m not a music theorist, I can’t know what musical wizardry Maria Camahort is using, but her musical style sounds balanced, distinctive and sophisticated and I hope she writes lots more. It is clear that the guitarist Ahmed Dickinson greatly believes in her work too.

During her video introduction she mentioned how long each piece takes to write. I forget how long exactly, but I remember I recalled to myself other composers I liked who were perfectionists: such as a composer called Maurice Durufle, another called Edward Bairstow. I wonder if she works on one at a time, or has lots in the pipeline.

Some of Maria’s music can be found here:

https://youtu.be/Dy5XS6h91Ks?si=SQ6e3z4tv5_QPrU3

I really enjoyed the concert and on the way back bought some Brick Lane bagels.

Modern Guitar Masterworks

Then last week was another concert, this time at the Royal Academy of Music. The concert was called Modern Masterworks for guitar. Three pieces were played by three guitarists. I connected most with the second piece, Oberon from Royal Winter Music by Hans Werner Henze. The piece was played by Georgi Dimitrov Jojo. Georgi made full use of the possibilities of the classical guitar, and I felt his performance was a masterclass in the use of possible tone colours and dynamics on the guitar. I also was intrigued about the sound of his guitar compared to the two others that were played, and would be interested to know its construction. If I find out, I will report back.

Georgi’s website can be found here: https://www.georgidimitrov-jojo.org/

Below are some notes on some other concerts I attended in Feb/March

Jack Hancher—Lunchtime Concert—London School of Economics —Having escaped in from the hustle of High Holborn, and navigated to the highest floor of the LSE, one found in Jack Hancher’s programme an oasis of calmness and beauty. Large portraits of stern accountants lined the walls, frowning down as Jack played pieces by Dowland, Debussy, Albinez, Snowden and more. The contrast between the busy city at lunchtime, and the quiet intimacy of Jack’s classical guitar playing, made exiting the LSE feel like passing back through some fae doorway, and one was left wondering whether it all really happened at all. Jack’s next London concert is in June. I look forward to returning to his realm.

Katalin Koltai— An event about the long collaboration between a guitarist, Katalin Koltai, and composer, Hans Abrahamsen, and the resulting music. At the heart of this talk was a composition called ‘Autumn’ - newly arranged for classical guitar—and a unique innovation for the guitar called the Open Frets guitar: a guitar with a built-in system of movable capos, expanding the possibilities of the guitar as an instrument. I enjoyed listening to the piece ‘Autumn’ by Hans Abrahamsen. I am inspired by autumn when I design and build my rosettes for my guitars (the pattern around the soundhole), and this piece did evoke images of those piles of fallen leaves that define autumn. I think the piece was aptly named. To learn more about the Open Frets guitar visit Katalin Koltai’s website and youtube channel.

The Oud and the Lute—Two players, Rihab Azar and Sergio Buchelli, performed on the oud and lute respectively, and spoke, along with the luthier Tony Johnson, on the long history, and differences between, the oud and the lute. It was fascinating to hear more about the oud, which is one of the oldest musical instruments, and remains popular in Arabic countries, though is not much known about it here. This was followed by a reception at the academy museum to celebrate the opening of an oud and lute exhibit.

I look forward to more enlightening guitar experiences. If there is a performance coming up that you recommend, in London or beyond, please do get in touch and let me know!